Some 100,000 books have been written about the American Civil War since it ended in 1865. That’s hardly surprising, given the four-year conflict’s impact on society, and not just because of the immense death toll, which new estimates put as high as 750,000 – more than the losses from all other wars combined. The effusion of blood created a new nation and a new mythology, anchored on the principles of freedom, equality and democracy.

There is not much room in this crowded field for Civil War neophytes. Erik Larson knows what he is about, however, in The Demon of Unrest – but do his critics? The mixed reception this book has received suggests not. As with his previous best-sellers, the author has taken a single event, the Battle of Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, in this case, and used it as a highly effective framing device for the immersive story he wishes to tell.

The actual event was a straightforward one. After holding out against Confederate forces for 108 days, the starving Union garrison relinquished its control of the fort on 13 April 1861. The battle was the point of no return, and although there hadn’t been any fatalities during the 34-hour bombardment leading up to it, a gruesome accident during the 50-gun salute did result in the first death of the war. Neither the Confederate besiegers nor the northern defenders of the fort had any inkling of the hell they were about to unleash on their fellow Americans.

This is not to say they were blindsided by the war. The country had been tearing itself apart over the issue of free vs slave labour ever since the invention of the cotton gin in the 1790s. Once slave-grown cotton could be efficiently cleaned and processed by machine, the South went from being an agricultural backwater to an economic powerhouse exporting four million cotton bales a year.

The production costs were cheap, the supply inexhaustible, and the southern states had a virtual monopoly on the global market. Unlike the northern states, they didn’t need immigration, education or industrialisation to grow rich – just millions of Africans, force-fed and force-bred into perpetual bondage. In the 1830s, southerners began referring to slavery as the ‘peculiar institution’, not because it was wicked and shameful, but on account of it being unique and inseparable from the southern way of life.

If northerners were at all uncertain about the non-negotiability of slavery – unlikely, given the political paralysis it caused in Washington – incidents on the floor of the Senate such as the Mississippi senator Henry Foote brandishing a loaded revolver and the South Carolina senator Preston Brooks beating the abolitionist campaigner Charles Sumner unconscious, helped to clear up any confusion.

International condemnation of slavery also fuelled southern bluster and arrogance. On the eve of the war, Britons were unamused to hear the South Carolina plantation owner James Hammond (rendered in gloriously repulsive detail by Larson) describe England as a vassal state in the southern empire. ‘Cotton is king,’ Hammond raged in a speech in 1858 that made him infamous on both sides of the Atlantic. ‘No power on Earth dares to make war on it.’ No power except the executive power of Abraham Lincoln, it turned out.‘Cotton is king,’ James Hammond raged in 1858. ‘No power on Earth dares to make war on it’

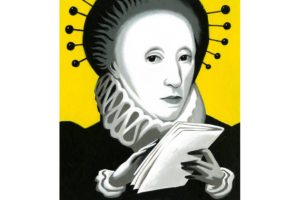

The pivotal role that individual action plays in momentous times is a recurring theme in Larson’s books. He is fascinated by two kinds of anti-heroes: the monster with a talent for propelling events, like Hammond, and the decent man whose limitations spur him towards catastrophe, like the professorial William Dodd, America’s ambassador to Germany the year Hitler came to power (In the Garden of Beasts, 2011). A colleague of Dodd’s later recalled he had seldom, if ever, ‘worked with a chief of mission who was more futile and ineffective’.In The Demon of Unrest, Larson’s anti-heroes are more starkly drawn. The decent men may be doomed to die, like Lincoln, or fail in their objective, like US Major Robert Anderson, the commander of Fort Sumter, but their flaws and limitations render them more, rather than less, admirable.

Lincoln was elected the first Republican president in November 1860 by a majority in the 34-state electoral college. But he lost the popular vote by a wide margin, giving the impression that his victory was an accident. His failure to address this added fuel to the claims of southern fire-eaters that he intended to destroy the South’s economy using high tariffs, ram abolition down their throats and set off a race war between blacks and whites.

Having never visited the Deep South, Lincoln was unaware of how entrenched the secession movement had become or how desperately pro-Union southerners needed support and leadership. Even more damaging for the prospects of peace was the traditional four months’ grace between the election and the inauguration. The General Assembly of South Carolina, the state with the noisiest supporters and longest history of secession attempts, voted to become an ‘independent commonwealth’ on 20 December 1860. Half a dozen more followed soon afterwards, yet Lincoln was still in Illinois in early February when the seven announced the formation of the Confederate States of America under President Jefferson Davis.

Lincoln only settled into Washington at the end of February, by which time another four states were preparing to secede, bringing the final total to 11. At his inauguration on 4 March, his belated attempt to cool secession fever by insisting he would defend the Union to his last breath while promising that slavery was safe in his hands alienated everyone. Southerners were convinced he was lying, even as abolitionists hoped that he was.

Initially, the majority of Lincoln’s cabinet felt certain he was not up to the job. Several tried to sideline him, sowing chaos among the already confused attempts to prevent disunion. Lincoln never altered his position, however, that slavery was a negotiable issue, but not Federal authority. Only two naval fortifications were still in Union hands by the time he took office: Sumter in Charleston and Fort Pickens in Pensacola, Florida. Back in December, John Floyd, Buchanan’s secessionist secretary of war, believed he had picked ‘one of us’ when he assigned a middle-aged southern officer from a slave-owning family to oversee Charleston’s fortifications. Major Robert Anderson’s rise up the ranks had stalled, despite an exemplary service record and being severely wounded in action during the Mexican-American War. He was teaching cadets at West Point when Floyd recalled him. It was not uncommon for such men to seek compensation by means of treachery. Anderson was the exception.

South Carolina’s secession was meant to have been the signal for Anderson to stand aside or evacuate his position. He did, slipping out under cover of darkness with a few dozen troops; but only to take up a stronger one. Although still under construction, Fort Sumter was the biggest of Charleston’s three forts. Anderson didn’t care about the rights or wrongs of slavery, nor did he care much about politics, but his honour and duty were sacred to him. To the indignation and fury of his now former brother officers, he made it clear that he would protect the Union flag flying over Sumter until he ran out of food or Confederate forces overwhelmed him.

In Larson’s dramatic rendering of the countdown to war, Lincoln was the one who cocked the starting gun by insisting that Major Anderson be resupplied, knowing it would provoke the Confederates; by engaging in a battle he knew he would lose, Anderson was the one who fired it. There’s an unmistakable aura of Greek tragedy to these men in The Demon of Unrest. They are reluctant heroes, forced to act the way they do because they are incapable of behaving in any other way.

It’s history as a form of catharsis, which leads to the deeper purpose of this work. The real project of the book may not be immediately divined from its soaring prose and ripping action scenes, yet it was shaped by the calamitous events at the Capitol on 6 January 2021. ‘I had the eerie feeling that present and past had merged,’ Larson writes in his foreword. It seemed to him as though America was once again in danger of slipping loose from its ideological moorings.

The Demon of Unrest is Larson’s attempt to call the country back to its senses. The book is not so much history in the traditional Thucydidean manner of causes and events, but rather a political argument posing as history in the manner of Xenophon, the father of popular narrative history. It is a full-throated defence of democratic values, individual agency and the power of collective action. Why read it? Because to understand the meaning of freedom for others is to know it in ourselves.