Few New Year’s resolutions actually make it past January. If everyone followed through on their resolutions, the consequences for humanity would be dire: The fast-food industry would collapse, the gym would become unbearably crowded, and lifestyle magazines would have nothing left to say.

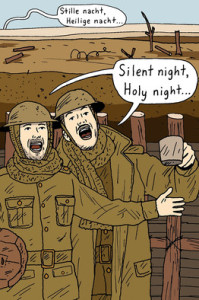

It is human nature to start off the year with a host of resolutions. The ancient Babylonians are known to have done it. The Romans even made a virtue of it, leaving us with January—named after Janus, the god of new beginnings.

The ancient Greeks, on the other hand, scorned the idea. It wasn’t humanity they doubted but the willingness of the gods to refrain from interfering in our affairs. “Men should pledge themselves to nothing, for reflection makes a liar of their resolution,” wrote Sophocles. Indeed, at the heart of almost every Greek myth was a warning of the terrible fate that awaited those who believed that all things were within their control. From Arachne to Oedipus, the message was clear: Don’t challenge the power of the gods lest you end up as a spider, or killing your father and marrying your mother.